For a review of Anthony McGowan's rivetting new YA novel set in the aftermath of Chernobyl, please follow the link to An Awfully Big Blog Adventure. (I should perhaps mention that it's mostly about the dogs of Chernobyl, not the people.)

Thursday, 29 September 2022

Monday, 12 September 2022

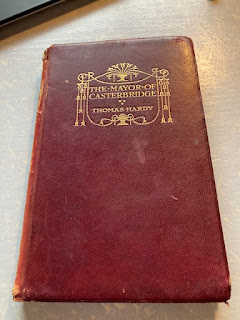

The Mayor of Casterbridge, by Thomas Hardy

I can't imagine why, but recently I've felt the urge to escape from the present into a greener, gentler past: and so I decided to re-read The Mayor of Casterbridge, by Thomas Hardy. I think Hardy had similar feelings; most of his books are set in a time slightly earlier than his own. His beloved Wessex included Dorset and parts of Wiltshire and Devon - all of which, of course, are still beautiful. Hardy had a strong sense of the past, and how its remains can be found in the present: hence, for example, the use of Stonehenge or somewhere very similar in Tess of the D'Urbervilles - and the Roman amphitheatre which is the setting for a number of clandestine meetings in The Mayor. And sure, it may be that he sometimes over-indulges in his preoccupation with such places, and with echoes through time.

It wasn't physically the easiest of reads. We have a set of leather-bound Hardy books which used to belong to my father-in-law, and at some stage when I was desperately trying to make some space on the bookshelves - this happens quite often - I chucked out most of my own, paperback copies of the novels on the ground that it was silly to keep duplicates. The copy of The Mayor dates from 1920, so about 25 years after the book was written. It's small, the paper is very thin, and the print at first sight is not easy to read. But I soon got used to it - as I became absorbed in the story.

It begins with an extraordinary incident, which is the springboard for all that happens later. Michael Henchard, a young farm labourer, is trudging the roads of Wessex with his wife, Susan, and their baby, Elizabeth-Jane. They are dispirited and weary. They happen upon a fair, and Susan suggests that, rather than going to the beer tent, they should go to a tent where furmity, a mixture of corn, milk, raisins and currants is sold. Susan's intent is in part to keep Henchard away from the beer - what she doesn't realise is that the furmity woman tips a measure of rum into the bowls of those who ask for it - which Henchard does.

Becoming steadily more drunk, he starts to bemoan his circumstances, and particularly his marriage. Outside the tent, he hears an auctioneer, and the idea strikes him that, just as he could sell a no-longer-wanted horse if he wanted, so he should be able to sell a wife he no longer wants. Others join in the 'fun', and an auction is set up, at which he sells Susan to a sailor for five guineas. What had started out as a cruel joke becomes reality; Henchard doesn't back down, and neither does the sailor. So Henchard wakes up the next morning with a blinding headache and the realisation that he has sold his wife. He searches for her and the sailor, but without success.

We next see our characters nearly twenty years later, when Susan and her daughter have come to Casterbridge in search of Henchard; the sailor has been lost at sea, and so Susan has decided she must seek out her former husband in the hope that he might be able to help them. Rural poverty is never far from the surface in Hardy: nor is the realisation that even a wealthy man, after a bad harvest, a poor business decision or an accident, can lose everything. They soon find out that Henchard is prosperous and has in fact become the Mayor of Casterbridge.

At the same time, a young Scot called Donald Farfrae has arrived in town. Where Henchard is dour and quick-tempered, Farfrae is quick-minded and pleasant; he's the sort of person who makes a success of everything he does, and draws people to him. Henchard quickly sees that Farfrae can be a great help to him, and he employs him.

So almost all the main characters are assembled. The remaining one is Lucetta, with whom Henchard has had an affair in the past: she arrives some time after the others, and so the scene is set.

Now, I'm not going to go into exactly what follows. For one thing that would spoil the story for you - but for another, it's very complicated! Suffice to say that things do not run at all smoothly for most of the characters - there is not a happy-ever-after for most of them. There are mishaps, there are misunderstandings, there are instances of petty revenge: but mostly, the tragedy arises from the characters of the protagonists and that one fateful evening in the furmity tent.

What really struck me was how clever the plot is. I think I noticed this particularly because, as a writer, I find plotting difficult. Not so Hardy. The structure of this book is like a maze - or like a fiendishly complicated sailor's knot. He is a master. The other thing that struck me is that you might think, from a relation of what happens, that this would be a melodrama. And it's not, though it does have elements of melodrama. Very often, a situation is set up, and you expect the character to be propelled into a self-destructive action - but instead, they stand back and consider, and react with restraint. (Then, just when you think it's safe to come out from behind the sofa, something else happens, and the disaster befalls the character anyway.)

And there is a happy ending. Sort of.

Monday, 5 September 2022

Pachinko, by Min Jin Lee

I do like a good long epic, and at over 500 pages, this is certainly that. I also like a book set in somewhere that I know little about, and again, this fits the bill: it starts in Korea and then moves to Japan.

Now, before I get going, a warning/apology: it's a few months since I read Pachinko, so this won't be as detailed as I'd like it to be. However, I'm sure I can tell you enough for you to decide whether you'd like to read it or not.

In preparation for this, I've just read the Q&A section with author Min Jin Lee which is at the end of the book. It's interesting, because, among other things, it shows how very well-qualified she is to write this book, which covers about 100 years of Korean/Japanese history: she lived in Korea till she was seven, then moved to America, and spent Five years in Tokyo when she was working on the book. (Another thing I liked was that her first published novel was the third book she had written. There's hope for us all.)

But perhaps the thing that struck me most was that she explains that she is predominantly interested in writing about the lives, not of the great and good, but of ordinary people. This strikes a chord with me. Up until recent times, ordinary (ie working class) people, have tended to leave far fewer traces of their lives than the wealthy. They have usually not written about their lives (mostly because they have not been able to write) or be written about. But that doesn't mean to see that they are any less intelligent than their wealthier peers, or their lives and relationships any less interesting. There is a poignant moment at the end of the book where the heroine, Sunja, visits her son's grave. The groundskeeper tells her he knew her son, who encouraged him to read and brought him translations of Dickens. He asks Sunja if she too has read Dickens, but she says quietly no - she cannot read. This is at the end of the 20th century.

The story starts with Hoonie and Yangjin, Sunja's parents. Hoonie has a cleft palate and a twisted lip, but he has a very sweet nature, and his parents own a boarding house which brings in a good income. So despite his deformities, the village matchmaker is able to find him a bride. The two young people are happy, but their first three children, all sons, die, and Sunja, the fourth child, is the only one to survive.

There is no point in telling you the ins and outs of what follows - best that you read it. Sunja grows up to be beautiful, and so the usual thing happens: she catches the eye of a wealthy businessman, becomes pregnant, and marries an idealistic young preacher. She and her family fall victim to war and economic hardship - and the ramifications of that early affair. No-one is wholly a villain: everyone (almost) tries their best. There are tragedies, but there is also happiness. I found it utterly absorbing.