For a review of Anthony McGowan's rivetting new YA novel set in the aftermath of Chernobyl, please follow the link to An Awfully Big Blog Adventure. (I should perhaps mention that it's mostly about the dogs of Chernobyl, not the people.)

Thursday, 29 September 2022

Monday, 12 September 2022

The Mayor of Casterbridge, by Thomas Hardy

I can't imagine why, but recently I've felt the urge to escape from the present into a greener, gentler past: and so I decided to re-read The Mayor of Casterbridge, by Thomas Hardy. I think Hardy had similar feelings; most of his books are set in a time slightly earlier than his own. His beloved Wessex included Dorset and parts of Wiltshire and Devon - all of which, of course, are still beautiful. Hardy had a strong sense of the past, and how its remains can be found in the present: hence, for example, the use of Stonehenge or somewhere very similar in Tess of the D'Urbervilles - and the Roman amphitheatre which is the setting for a number of clandestine meetings in The Mayor. And sure, it may be that he sometimes over-indulges in his preoccupation with such places, and with echoes through time.

It wasn't physically the easiest of reads. We have a set of leather-bound Hardy books which used to belong to my father-in-law, and at some stage when I was desperately trying to make some space on the bookshelves - this happens quite often - I chucked out most of my own, paperback copies of the novels on the ground that it was silly to keep duplicates. The copy of The Mayor dates from 1920, so about 25 years after the book was written. It's small, the paper is very thin, and the print at first sight is not easy to read. But I soon got used to it - as I became absorbed in the story.

It begins with an extraordinary incident, which is the springboard for all that happens later. Michael Henchard, a young farm labourer, is trudging the roads of Wessex with his wife, Susan, and their baby, Elizabeth-Jane. They are dispirited and weary. They happen upon a fair, and Susan suggests that, rather than going to the beer tent, they should go to a tent where furmity, a mixture of corn, milk, raisins and currants is sold. Susan's intent is in part to keep Henchard away from the beer - what she doesn't realise is that the furmity woman tips a measure of rum into the bowls of those who ask for it - which Henchard does.

Becoming steadily more drunk, he starts to bemoan his circumstances, and particularly his marriage. Outside the tent, he hears an auctioneer, and the idea strikes him that, just as he could sell a no-longer-wanted horse if he wanted, so he should be able to sell a wife he no longer wants. Others join in the 'fun', and an auction is set up, at which he sells Susan to a sailor for five guineas. What had started out as a cruel joke becomes reality; Henchard doesn't back down, and neither does the sailor. So Henchard wakes up the next morning with a blinding headache and the realisation that he has sold his wife. He searches for her and the sailor, but without success.

We next see our characters nearly twenty years later, when Susan and her daughter have come to Casterbridge in search of Henchard; the sailor has been lost at sea, and so Susan has decided she must seek out her former husband in the hope that he might be able to help them. Rural poverty is never far from the surface in Hardy: nor is the realisation that even a wealthy man, after a bad harvest, a poor business decision or an accident, can lose everything. They soon find out that Henchard is prosperous and has in fact become the Mayor of Casterbridge.

At the same time, a young Scot called Donald Farfrae has arrived in town. Where Henchard is dour and quick-tempered, Farfrae is quick-minded and pleasant; he's the sort of person who makes a success of everything he does, and draws people to him. Henchard quickly sees that Farfrae can be a great help to him, and he employs him.

So almost all the main characters are assembled. The remaining one is Lucetta, with whom Henchard has had an affair in the past: she arrives some time after the others, and so the scene is set.

Now, I'm not going to go into exactly what follows. For one thing that would spoil the story for you - but for another, it's very complicated! Suffice to say that things do not run at all smoothly for most of the characters - there is not a happy-ever-after for most of them. There are mishaps, there are misunderstandings, there are instances of petty revenge: but mostly, the tragedy arises from the characters of the protagonists and that one fateful evening in the furmity tent.

What really struck me was how clever the plot is. I think I noticed this particularly because, as a writer, I find plotting difficult. Not so Hardy. The structure of this book is like a maze - or like a fiendishly complicated sailor's knot. He is a master. The other thing that struck me is that you might think, from a relation of what happens, that this would be a melodrama. And it's not, though it does have elements of melodrama. Very often, a situation is set up, and you expect the character to be propelled into a self-destructive action - but instead, they stand back and consider, and react with restraint. (Then, just when you think it's safe to come out from behind the sofa, something else happens, and the disaster befalls the character anyway.)

And there is a happy ending. Sort of.

Monday, 5 September 2022

Pachinko, by Min Jin Lee

I do like a good long epic, and at over 500 pages, this is certainly that. I also like a book set in somewhere that I know little about, and again, this fits the bill: it starts in Korea and then moves to Japan.

Now, before I get going, a warning/apology: it's a few months since I read Pachinko, so this won't be as detailed as I'd like it to be. However, I'm sure I can tell you enough for you to decide whether you'd like to read it or not.

In preparation for this, I've just read the Q&A section with author Min Jin Lee which is at the end of the book. It's interesting, because, among other things, it shows how very well-qualified she is to write this book, which covers about 100 years of Korean/Japanese history: she lived in Korea till she was seven, then moved to America, and spent Five years in Tokyo when she was working on the book. (Another thing I liked was that her first published novel was the third book she had written. There's hope for us all.)

But perhaps the thing that struck me most was that she explains that she is predominantly interested in writing about the lives, not of the great and good, but of ordinary people. This strikes a chord with me. Up until recent times, ordinary (ie working class) people, have tended to leave far fewer traces of their lives than the wealthy. They have usually not written about their lives (mostly because they have not been able to write) or be written about. But that doesn't mean to see that they are any less intelligent than their wealthier peers, or their lives and relationships any less interesting. There is a poignant moment at the end of the book where the heroine, Sunja, visits her son's grave. The groundskeeper tells her he knew her son, who encouraged him to read and brought him translations of Dickens. He asks Sunja if she too has read Dickens, but she says quietly no - she cannot read. This is at the end of the 20th century.

The story starts with Hoonie and Yangjin, Sunja's parents. Hoonie has a cleft palate and a twisted lip, but he has a very sweet nature, and his parents own a boarding house which brings in a good income. So despite his deformities, the village matchmaker is able to find him a bride. The two young people are happy, but their first three children, all sons, die, and Sunja, the fourth child, is the only one to survive.

There is no point in telling you the ins and outs of what follows - best that you read it. Sunja grows up to be beautiful, and so the usual thing happens: she catches the eye of a wealthy businessman, becomes pregnant, and marries an idealistic young preacher. She and her family fall victim to war and economic hardship - and the ramifications of that early affair. No-one is wholly a villain: everyone (almost) tries their best. There are tragedies, but there is also happiness. I found it utterly absorbing.

Monday, 29 August 2022

A Whole Life, by Robert Seethaler

This is not one of my Mr B's subscription books - it's a book I suggested for a recent meeting of the book group I belong to. We wanted a short book for this session, and A Whole Life fitted that bill

My copy is a hardback, and it's rather lovely - I like the design of the cover, which is in white, black, and soft shades of green. The image looks to me like the sea, with heaving, foam-flecked waves. But it isn't the sea, it's a mountain. On the top of it is an alpine hut, and if you look carefully, you can see about a third of the way up a tiny figure of a climber wearing a backpack. He isn't noticeable, but there he is: he has a long way to go, but he's climbing steadily up.

And that really reflects the story. Andreas Eggar is born in a mountain valley. (Seethaler was born in Austria, so I think we can place the valley there.) An orphan, at the age of four he is put into the care of an uncle, a farmer called Kranzstocker, a cruel man whose only interest in the boy is how much work he can get out of him. He beats the child for the smallest of transgressions - spilt milk, a mistake in an evening prayer. One time. he beats him too hard and smashes the bone in his leg, as a result of which Andreas has a lifelong limp.

So Andreas has a tough, even brutal life from the beginning. Even when he marries, and seems at last to have found happiness, fate - and the mountain - intervenes. When he goes to fight, he is captured and held by the Russians for several years after the war has ended. But somehow, it's not a sad book. He never forgets his wife and no-one ever replaces her, but he just keeps on, like the figure on the cover image trudging up the mountain. When he returns from Russia, things have moved on and his old job with a cable car company no longer exists - so he simply finds something else to do, somewhere else to live. He is immensely stoical. He keeps on keeping on, because really, that's all you can do.

Before I went to my book group meeting, I knew that I liked the book, but I couldn't articulate why. But as we talked, it emerged that several of us had been through tough times lately. One of us had recently lost her father, and she talked about that, and how it had been. She said that yes, of course it was tragic - but everyone has tragedies in their life. And in the end, like Andreas Eggar, the thing you have to do is keep on. I talked about my fear of heights: she remembered climbing Mount Kilimanjaro. She wasn't a mountaineer, she said: "But really, it's remarkable what you can do if you just keep putting one foot in front of the other." (If anyone's read my book Jack Fortune and the Search for the Hidden Valley, you may remember that that's exactly what Jack has to learn, when he finds out, while plant-hunting in the Himalayas, that he is - inconveniently - afraid of heights: you must just keep putting one foot in front of the other.)

So, I think that's what chimes with readers of A Whole Life. Here is a man, a very ordinary man in terms of possessions and achievements, who has nevertheless triumphed and, in the end, lived a life he's pleased with. He's known the beauty of nature - and he's also known its cruelty. He's known love - but he's also known loss. And yet, despite all life's thrown at him, he's just kept going.

Monday, 22 August 2022

Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead

For my last birthday, I was lucky enough to be given a book subscription from Mr B's Emporium in Bath. (Thanks to my son for this incredibly generous present!) Each month, I receive a beautifully packaged book, chosen for me by one of their booksellers after an initial consultation about the kind of books I like. What I should have done, of course, was to have written some notes about each one as I finished it. I didn't do that, so now I'm playing catch-up.

|

The Great Circle was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and also for the Women's Prize for Fiction. It's a novel about Marian Graves, a (fictional) early female aviator - a contemporary of Amelia Earhart. It's a huge novel which is fitting, because the peak of Marian's flying career is her attempt to fly the Great Circle - to circumnavigate the globe.

Marian's profound love of flying is at the heart of the book, but it takes in much more: set mostly in America, it takes in a good deal of the twentieth century. The story starts, not with a plane, but with a ship: the Josephina Eterna. The owner's wife, Matilda, is given the job of launching the ship - but she is perturbed: the ship is named after her husband's mistress, and also, no-one has explained to her exactly what she has to do. The captain, Addison Graves, tries to help her, but the bottle misses its target: a bad omen. A few years later, the ship sinks. Many passengers are lost, and Graves takes the blame, though the fault was really the owner's. As a result, he spends several years in prison, and his two children, of whom Marian is one, are sent into the care of his kindly but rather feckless brother.

When he comes out of prison, he briefly comes to see his children, but then fades away again, leaving behind him crates full of his belongings - books and mementoes of his travels. Marian is fascinated by the accounts of explorers and travellers - especially those who go to the far north - and so the seeds are set for her love of adventure. As a teenager, she has a flight in a plane which is part of a travelling show, and she is hooked. She gets to know an older man, wealthy but ruthless, who will finance her flying if she will marry him. She makes the deal, but eventually needs to attain freedom, and flies north.

And so her story continues, taking in a stint in Britain during the war taxi-ing planes for the RAF.

But there is also another, secondary heroine, a film star called Hadley. Her story is contemporary. She is something of a lost soul, caught up in various scandals. She is playing the part of Marian in a film, and becomes fascinated by her. Marian's great circumnavigation ended, apparently, in disaster: Hadley's own parents died when she was young in a plane crash. Clearly, there are parallels.

I do see the need for this parallel story - I think. It provides a way of exploring what happened to Marian, and makes it into a mystery story with all the tension and suspense which that entails. But I didn't like Hadley as a character. She's selfish, shallow and uncaring - or so she seems to me - and I didn't like being in her company. But she takes up a relatively small part of the book - and from other reviews that I've read, other readers don't have the same reaction to her as I did. So don't be put off by my dislike of Hadley - you probably won't feel the same about her, and anyway, there is so much more to enjoy in this book. The prose, for one thing - it is beautifully written. Here, for example:, is the first paragraph:

I was born to be a wanderer. I was shaped to the earth like a seabird to a wave. Some birds fly until they die. I have made a promise to myself: My last descent won't be the tumbling helpless kind but a sharp gannet plunge - a dive with intent, aimed at something deep in the sea.

Saturday, 2 July 2022

Donna Leon - the Inspector Brunetti series

These are times such as I never expected to see. I've written several books set during the second world war; I've listened to the stories told me by my father, who was a prisoner of war in Poland for five years. (Incidentally, he told me once that the worst thing he saw in the war was the lines of refugees, trudging along roads carrying everything they could, not knowing where they were going. I've thought about that a lot lately.) I've wanted to know why wars happen, why dictators become monsters. But it was always an exploration of the past; I never expected to see a replay in real time.

I've watched the news and read articles. But there are times when I just want to find a safe place to retreat to, to shut myself away from it all. And one of the ways to do that, I find, is to read - and perhaps paradoxically, to read detective series. They have to be the right kind. I don't want detailed descriptions of horrible ways to kill - I don't want serial killers. In fact, the murders which are usually the inciting incidents don't really interest me that much at all. It's the community of characters I like, and often the setting too: it's the way the characters build and develop over the arc of the series - the way they change. This is true of several of the series I've written about on this blog: Montalbano, the Colin Cotterill books, Louise Penny's Inspector Gamache series, and of course, the wonderful Ruth Galloway books by Elly Griffiths.

|

| Photo from the Sydney Morning Herald |

So recently I've returned to Donna Leon's series set in Venice, which stars Inspector Guido Brunetti. Many of the detectives who head up series are in some way flawed or damaged: think Robert Galbraith, Inspector Rebus, Simon Serailler. Not so Guido Brunetti. He is a happy family man, who has an excellent relationship with his wife, Paola (an academic who loves Henry James and is a wonderful cook) and their two children. He is kind, decent, and clever: he reads classic Greek and (I think) Roman literature as a way of relaxing.

His staff are nice people too - with the exceptions of his boss, Patta, who is vain and ambitious, and useless at catching criminals, and Lieutenant Scarpa, who is a very nasty piece of work indeed. But neither of them is a match for Signorina Elettra. She is Patta's secretary, but she's far more than that. She's very clever, very well-connected and always beautifully dressed, and she conspires with Brunetti to solve crimes despite the inept bumbling of Patta and Scarpa. She recognises the power of the internet very early on, before most of the others even know how to use a computer.

What you will not get from these books is intricate plotting. Indeed, the crime is hardly even a central feature - though it may be a useful way to explore a particular problem in Venetian/Italian society, such as corruption (quite often), politics, the treatment of immigrants, and so on. Sometimes, you feel at the end that things have not been satisfactorily resolved - which is often the case in real life, but not usually so detective novels. But there are so many other riches that perhaps this doesn't really matter too much: the Venetian setting, for instance. And the mouth-watering descriptions of food, which is tremendously important to Brunetti. It's mostly the characters, though, which are the draw.

Monday, 25 April 2022

The Women of Troy, by Pat Barker

Sunday, 9 January 2022

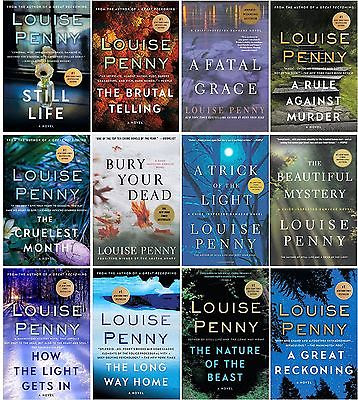

The Inspector Gamache series, by Louise Penny

A couple of months ago, a friend put me onto a detective series by a writer I hadn't heard of, Louise Penny. They're set in Canada, she said, in Quebec. I think you'll like them.

Well, sixteen books later, I can confirm that she was absolutely right. (There is a seventeenth, but it's still expensive on Kindle, so I'm trying to exercise a little self-discipline and wait till the price comes down.) I thoroughly enjoyed these books. What's more, they did me good - they were therapeutic.

And why?

Well, I find autumn a difficult season. Nothing complicated about that: it's the dark nights, it's the sense that not only is winter coming, but it's going to be hanging around for months and months. As days shorten, so my mood sinks. For this time of year, I need reading which is both engrossing and comforting.

And although these are ostensibly murder mysteries, they are comforting. For the most part, the characters they feature are nice. They're quirky, kind, funny and witty. Take Inspector Gamache himself. He is not your usual star of detective series; he's not miserable, he doesn't have a fatal flaw - he has friends, for heaven's sake, and a happy marriage. He's big, strong, gentle, perceptive and kind - but if you need someone strong and decisive when push comes to shove, he's the one I'd choose over Rebus, Simon Serailler, Albert Campion - even Dr Siri. (Not sure who I'd pick between him and Elly Griffiths' Nelson, though - that would be a close call.)

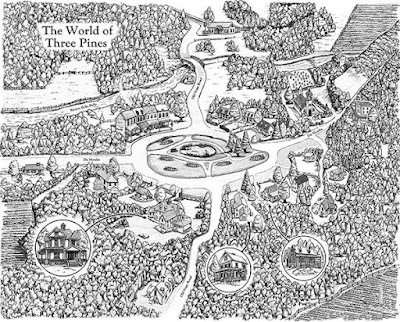

But he's not the only star of this series. That would be the village of Three Pines, which has a magical quality about it - a touch of the Narnias. For a start, it's not to be found on any map, and it's not discoverable by GPS. It's small, it nestles among fairy-tale forests, and in the winter it snows and is beautiful. It's inhabited by a bunch of eccentric friends. They're not all faultless, not by any means: some of them do bad things. But somehow they're all people you'd love to have as your friends - even Ruth, the crazy old poet who insults everybody and is only nice to her pet duck. Gamache comes across the village on an early case, and eventually ends up living there. Along the way, apart from the murders he has to solve, he encounters corruption in the police force which almost destroys him, terrorism, difficulties with his son; but nothing dents his belief that people are essentially good - indeed, he's known for choosing as colleagues people whom everyone else has given up on: they inevitably come good in the end, and are fiercely loyal to the Chief.

So why are the books so comforting? Well, the belief in kindness and goodness clearly helps. So does the version of winter, which is so much more magical than the dank, damp and dreary variety which we see so much more of. The stories are gripping, and the conversation is funny and sharp - it's as if you're in the company of a bunch of a delightful group of friends, who will always be able to entertain you.

And then there's the food. There is so much wonderful food. The owners of the bistro and guesthouse, Gabri and Olivier (I think that's his name, but may be wrong) produce the most delicious snacks and meals at the drop of a hat, but they're not the only ones; everyone seems to have their own speciality, except Ruth, who simply helps herself to what everyone else cooks. There are croissants, and brownies, and masses of maple syrup, and sandwiches with the most gorgeous fillings, and spicy soups - well. Who wouldn't want to live in Three Pines, despite the high incidence of murder?

If you haven't been there yet, do drop in. See you in the bistro.